#003 - Wanda (1970)

/Wanda (1970)

Directed by Barbara Loden

Starring Barbara Loden, Michael Higgins, Dorothy Shupenes, Peter Shupenes, Jerome Thier

Written by Barbara Loden

DP: Nicholas T. Proferes

Edited by Nicholas T. Proferes

Wanda doesn't know what she wants. Wanda has a desire for a connection, for love, for sex. But Wanda doesn't really ever feel much. Wanda is often tired. And hungry. If there is a man willing to take her (not necessarily take care), she jumps at the opportunity, hoping it will give her something, make her feel anything. Wanda is lost. When she's among people, she still feels lost. Wanda meets a man. The man allows her to be with him. The man is not nice to her. The man's name is Norman. He isn't nice to anyone, really. He seems to enjoy being mean. Wanda accepts abuse. Wanda accepts anything. Wanda doesn't know when she became the way she is. Wanda doesn't know how it will end. Wanda keeps going, tired, hungry, lost.

If Wanda is viewed as representative for women in film in the 1970s, then it is a very bleak outlook. Wanda, the protagonist, lacks any agency. She can only imagine existing as being paired with a man, no matter what kind of man it is. Any psychoanalysis would fail, because Wanda lacks the ability to reflect, which makes her seem shallow, empty, lifeless. The movie does not tell us but we can only imagine what kind of trauma she must have suffered to become this numb and needy.

The film is not easy to watch because it avoids any narrative structure that would give us hope that Wanda is on an arc. But she flatlines, being in the same position in her life as in the beginning, lonely among people, aimless, anxious. It is a character study about a character who doesn’t give us much insight because she seems to lack that insight herself. Which does not mean we can’t learn something from observing her journey, even if she does not seem to learn anything herself. There are moments of resistance, as in a moment when a man tries to sexually abuse her and she flees.

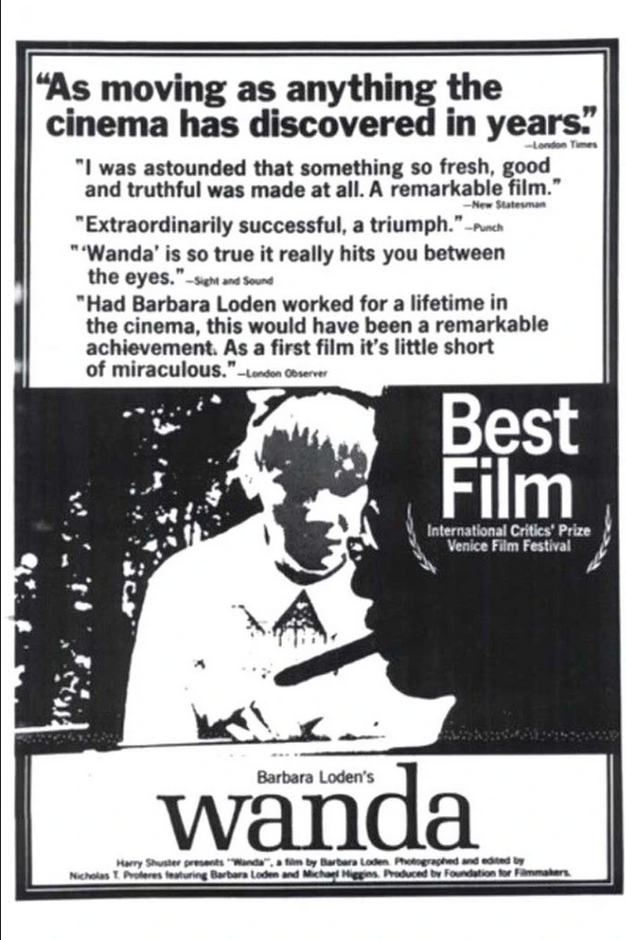

Barbara Loden directs herself in an astonishing performance. The film might seem amateurish on first glance but is actually carefully thought out and written, with Loden commanding every frame behind and in front of the camera. Loden said, that she was partly inspired by a news story about a woman arrested for being an accomplice in a bank heist, but also by her own life. Married to superstar director Elia Kazan, she managed to step out of his shadow to make this incredible film, winning an award in Venice. Kazan acted as he if was one of the men in her film, trying to downplay her talent and bolstering his own contributions. It seems hard to imagine that Kazan would be able to do any of the things Loden pulls off here. Unfortunately, Loden never managed to make a career out of this impressive debut film.

She still became something of a pioneer for female filmmakers in the 70s, not just because of her talent, but also because of telling such a strictly feminist film where only the ignorant critic would not see that Wanda is a product of a misogynist, patriarchal world, in which her character eventually gives up by allowing men to push her around, wherever they want.

What followed, were many similarly themed films directed by women in the 70s: Nathalie Granger (1972, Marguerite Duras) depicted a similarly bleak world, in which women and men seemed to be engaged in permanent conflict (with the women winning this time). The Night Porter (Il portiere die notte, 1974, Liliana Cavani) showed another woman used and abused by men, here in the context of the Holocaust. Swept Away (Travolti da un insolito destino nell'azzurro mare d'agosto, 1974 Lina Wertmüller) drove the battle of the genders to extreme heights of shouting and raping. And then of course, Jeanne Dielman (1975, Chantal Akerman) played out as if it was Wanda’s soul sister, with another woman drifting aimlessly through life while occasionally bumping into men, just with a very different end result. Barbara Loden might not have managed to tell more stories, but Wanda’s spirit lives on.

While Wanda has been ignored by every major text of feminist film theory published in English over the last 20 years, Akerman, Potter and Rainer have become household names.[…] Yet, there is a major, poignant difference between the two films, one that may explain why Jeanne became a feminist heroine par défaut andWanda easily forgotten. In Akerman’s film, men are peripheral; they are mouths to be fed, cocks to be satisfied, but the film hints at the possibility of a utopian space structured by women's desires, stories, needs and anxieties. Jeanne would never address any of her tricks as “Mister”, and Akerman didn't make her film under the terrifying gaze of one of Hollywood's sacred monsters. In Wanda's narrative space, however, men cast a giant shadow. (Reynaud 2004)

Winner of the Pasinetti Award at the Venice Film Festival for Best Foreign Film

Sources:

Longworth, Karina (March 17, 2011). One-Hit Wanda. LA Weekly.

Reynaud, Bérénice (2004). For Wanda. In: Elsaesser, T., Horwath, A., & King, N. (eds.). The Last Great American Picture Show: New Hollywood Cinema in the 1970s. Amsterdam University Press.